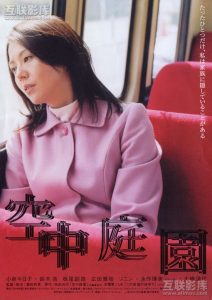

In class, I had my students read Chin Music Press’ excellent Kûhaku and other stories from Japan (2004) paired up with watching “Hanging Garden” or Kûchû Teien (2005). Where Kûhaku gives a broad spectrum of personal narratives concerning Japan, from both native and gaijin perspectives, Kûchû Teien is kind of a Japanese “FUBU” (For Us, By Us) movie that contains a strong social commentary.

In class, I had my students read Chin Music Press’ excellent Kûhaku and other stories from Japan (2004) paired up with watching “Hanging Garden” or Kûchû Teien (2005). Where Kûhaku gives a broad spectrum of personal narratives concerning Japan, from both native and gaijin perspectives, Kûchû Teien is kind of a Japanese “FUBU” (For Us, By Us) movie that contains a strong social commentary.

At the same time, Kûhaku is a fantastic little book. The binding is a thick, grey canvas, embossed with color and thick, black lettering. The inner leaves are crimson, and the pages are at least 40# weight. The text of the book is a bit charcoal, on paper that has more of a yellowish tinge. There are color pages, especially in the poem/graphical journey for which the book is named. Kûhaku leaves the reader feeling uneasy, as if something is out of place. It is akin to that jet-lagged feeling you get after step off the plane at KIX, expecting it to be early in the morning, but the sun is just getting ready to set. Some essays deal with the Marxist superstructure/dialectic tension of a Confucian society. Others flat out vomit up honne when you are least expecting it. Especially engaging is David Cady’s Canned Coffee, where he chronicles the experiences he had whilst enjoying…er…imbibing various types of canned coffee. Equally valuable are the “Floating Feeling” series; three essays that explore the plight of various Japanese housewives. Also, Roland Kelts’ Oyaji Gari piece is most helpful, especially when dealing with the concept of きれる (kireru): losing it when you can’t take the pressure any longer.

Reading Kûhaku in conjunction with “Hanging Garden” is especially suitable for understanding Eriko’s (the main character’s) plight. Eriko lives in a fantasy world she has created for herself because she finds her own lived experiences to be too painful to accept as “reality.” She has schemed to build the “perfect” family where no one has any secrets, true honne, if you will, but ends up being completely false and “obsessed” with the lie she lives. Her husband cheats on her with a variety of women. Her daughter is trying to experiment with boys. Her son is almost a hikikômori, or shut-in, who lives in the simulation of reality he has created for himself on his macbook. Her mother is a bit of a free-spirit, and old baba who speaks her mind and is not afraid to make waves. Each member of the family has some major societal disfunction; but by the end, the family realizes its pretenses and resolves their problems in a tepid way. The movie is just claustrophobic, with an almost-happy ending; a good example of a superflat movie that deals with the postmodern social issues that some families face. There is hope at the end, but built on what? Trust? Faith? Faithfulness? Freedom? More like old-fashioned Confucian resolve and some phenomenological twists. The mother is reborn after she leaves her womb of her false reality, and the family is there for her to re-engage. But at what cost?

Some have compared it to American Beauty, and I think this is a fair assessment. It is important to examine postmodern Japan through the lens Japanese themselves are using to understand their own context. Instead of jumping to conclusions and saying, “All Japanese are X,” it is better to say, “These types of problems exist in society, and here is how some Japanese understand them.” As westerners looking in, we always run the danger of fetishizing or synecdochizing Japan based on slivers of stories that make their ways to our shores.

Disturbing, endearing, and enchanting, I cannot recommend these works enough.