One of the texts I am working through for my dissertation is Uchimura Kanzō’s Consolations of a Christian. It has never been translated into English before, outside of the two chapters I have translated recently (and a few bits here and there by John Howes and others.)

One of the things I have discovered is just how well read Uchimura was. For instance, in his discussion of failure in his vocation, he devotes a few pages to the story of Henry of Navarre, the “prince of the blood” who came into conflict with the French throne due to his protestant (Huguenot) faith. Uchimura provides many historical details, and even creates an interior monologue for Henry, who was agonizing over whether to end hostilities and bow to the Papacy, or keep fighting for the freedom of the Huguenots. As he ended hostilities, France flourished, and Henry’s Edict of Nantes proclaimed religious freedom throughout France. But, after he died, through the actions of Cardinal Richelieu and others, Roman Catholicism regained its supremacy in the land, and later kings, according to Uchimura, failed in their duties to keep order and peace in France as they did not regard the people and continued to enrich themselves. The ultimate result was the French Revolution. Uchimura concludes that Henry never really loved France since he capitulated, and his capitulation led to the disasters that culminated in Napoleon. Later in the chapter, Uchimura quips that Cromwell may have failed in his attempts to create a more just society, but after his death, the foundation that the unwavering Cromwell laid for democracy and equality shows his actual success. Through his work, Cromwell prevented the revolutions of the 18th century Europe from rocking England.

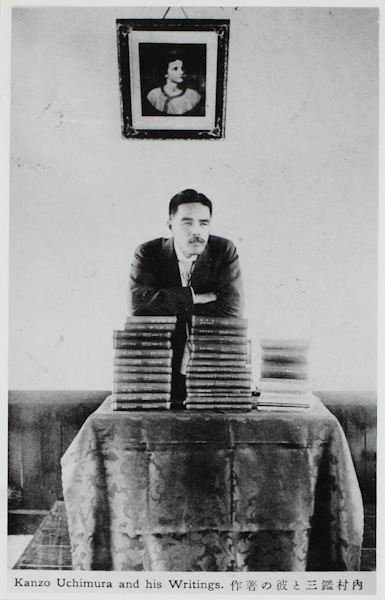

What were Uchimura’s sources? In my archival work at the Uchimura Kanzō collection at Hokkaido University, I was able to track down what Uchimura was reading and garner much from his marginalia in his Carlyle collection and his Dante. He often quotes Carlyle, (and in the case of Chapter 5 of the Consolations, that makes sense when it comes to his ideas about Cromwell, whom Carlyle praised mightily), but why did he think Henry of Navarre was a failure and that his capitulation caused the downfall of France? This is somewhat unusual in terms of how we think of history…after doing a little digging, I discovered Samuel Smiles’ The Huguenots: Their Settlements, Churches & Industries in England and Ireland

Smiles–ever the promoter of Protestantism, ever the English patriot–had similar ideas to Carlyle about the role and heritage of English politics in the world. Smile’s narration of events and their outcomes certainly prefigures Uchimura’s. How many contemporary readers have much experience with Carlyle or Smiles? Thanks to digital texts, we can enjoy them now!

But what fascinates me is how Uchimura used these English texts to discuss his own failures vis-a-vis his work and how society viewed his legacy. He brought them to a Japanese audience, then used them to discuss his Christian worldview. Then he communicates his sense of what Japan’s mission in the world should be (bringing culture and enlightenment after social reform). Uchimura, like these faithful figures of old, wanted to hold fast to his sense of conviction and bring his ideas into the future as an inheritance. In addition, he connects the faith of Cromwell, Huss, and others, to Kusunoki Masashige, the faithful retainer who would give his life in the service of the restoration of Godaigo. Late Edo and early Meiji thinkers, as Varley tells us, pointed to Kusunoki as a paragon of loyalty and a key figure in restorationist ideas. He died in service of his conscience. Though Fukuzawa Yukichi called him a failure, others who came after Kusunoki following his example, were latter-day Kusunokis, true patriots, true supporters of the imperial line. Uchimura ties himself to this love of country, and love of his God: being faithful despite failure is actually success.